SOUTH BEND, Ind. — Twenty years ago, Asian carp imported by Southern fish farms began their high-profile journey along the mighty Mississippi River toward southern Lake Michigan in Chicago, their most probable entry point into the Great Lakes.

Now, some of the most important research to help fend them off is being generated inside the University of Notre Dame’s Galvin Life Sciences Center, barely more than a Hail Mary pass from the school’s iconic football stadium.

The relatively nondescript academic hall is home to Notre Dame’s department of biological sciences — but also some of the Great Lakes region’s top science nerds, who have used laboratories there since 2009 to invent and improve upon a cutting-edge research technique that is quickly becoming one of the most powerful tools for detecting microscopic bits and pieces of fish, plants, aquatic insects, and other organisms in our waterways.

Called eDNA, for environmental DNA, the process developed six years ago was as much of a watershed moment in the ongoing battle against fugitive fish as the great Mississippi River floods of 1995 that made water levels so high that Asian carp escaped from Southern fish hatcheries that had imported them to eat pond scum.

Think of it as forensic detective work involving fish genetics.

Asian carp pose one of the worst threats ever to the Great Lakes region’s $7 billion recreational and commercial fishing industries, the backbone of thousands of jobs and a lake-based tourism industry worth about $12 billion a year in Ohio alone.

A game changer

Scientists have long characterized and assessed what’s on land, mostly from what they find in animal feces.

But until eDNA was developed, that wasn’t being done at the microscopic level in the water column. Such material is typically fish scales, cells, feces, or mucus found in the top 2 inches of the water column.

Under the direction of David Lodge, director of the Notre Dame Environmental Change Initiative, researchers in 2009 developed eDNA for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The agency requested it to help hunt for any Asian carp evidence near Chicago — apparently not realizing at the time how eDNA was going to become a game-changer.

When the corps got an unexpected result — Asian carp DNA beyond Chicago-area electrical barriers the government operates to keep invasive fish out of Lake Michigan — Mr. Lodge was ordered to defend the process in court.

The eDNA method of detecting genetic material was ruled scientifically accurate, despite the corps’ challenge. It was peer-reviewed and published in Conservation Letters, the flagship academic journal of the Society for Conservation Biology, and was vetted by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

In subsequent years, U.S. Fish and Wildlife scientists — using Notre Dame’s eDNA technique — have found Asian carp eDNA in many more Chicago-area water samples, as well as many drawn from western Lake Erie and other parts of the Great Lakes region — including the Maumee River in downtown Toledo.

Wake-up calls

The big question is how anecdotal or alarming those discoveries are.

While no live Asian carp have been found in tandem with the relatively new era of eDNA sampling, three older bighead species — possibly illegal releases — were caught by commercial fishermen in western Lake Erie between 1995 and 2000. Two were taken from Ohio water and one near Ontario’s Pelee Island, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

Biologists aren’t so much concerned about an errant fish or two, but any evidence of a breeding population.

So far, there is none.

Theories for the presence of Asian carp eDNA exist, many of which seem implausible to scientists familiar with the technique.

They believe the most probable explanation for the genetic material is the presence of live fish.

There could be feces in the water from birds that have fed on Asian carp elsewhere. DNA could be unknowingly transported on hulls of recreational boats; researchers who know better say they bleach theirs. It’s even conceivable, though unlikely, samples might be picking up effluent from sewage-treatment plants miles away, Mr. Lodge said.

All positive hits are considered wake-up calls.

Complex, yet simple

Lindsay Chadderton, aquatic invasive species program director for the Nature Conservancy’s Great Lakes Project, puts eDNA into perspective with this analogy:

“When the smoke detector goes off, do you just assume it’s the toaster? It’s about our risk and our ability to respond,” he said. “If you choose to ignore, what are the consequences?”

Mr. Chadderton is credited by Mr. Lodge as the one who came up with the idea for developing the eDNA technique, based on information from a French research paper.

The technique is one many laymen would have trouble explaining in great detail. But to scientists, according to Mr. Lodge, he and others are befuddled as to why they didn’t think of it before.

“The simplicity of this blew us away,” he said. “There’s a lot more DNA in the water than there is individual organisms. All we’re doing is trying to say the species is there.”

It basically consists of having water samples pass through a super-refined filter to remove tiny bits of what Mr. Lodge calls “stuff” from the water column — particulate matter too small to be seen by the human eye.

That matter goes through a series of machines that help separate eDNA from other material and, ultimately, characterize what’s in the water.

Researchers see greater potential in eDNA if it’s used to find more than just Asian carp genetic material in water.

It could possibly, for example, be used to help characterize aquatic life in ditches, streams, and wetlands where more specific data is needed to help settle development controversies, Mr. Chadderton said.

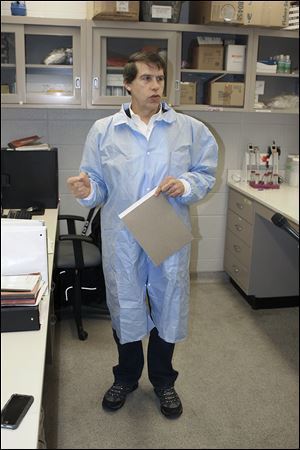

Much of the broader research is being undertaken in a lab headed by Mike Pfrender, associate professor of Notre Dame’s biological sciences.

He talks with enthusiasm when he explains how the “eDNA revolution” has provided scientists new and amazing data on a “huge diversity of microbes” and how he sees the technology improving “in leaps and bounds” within a few years.

How sophisticated is it? Microchips a little larger than a dime hold 50 million DNA sequences. By crunching that genetic data into a more workable size, scientists get a better idea of what fish, plants, or other species are likely nearby.

The chips are inserted into a machine that cost $500,000, one that is about to be replaced by a next-generation device that will be capable of doing far more — quantifying down to single molecules, Mr. Pfrender said.

“It shows us who’s in a community and if there are any new ones,” he said.

Cleanups ordered by the U.S. EPA are often based on the diversity of impaired fish, plants, aquatic insects, and other species. Traditionally, that involves labor-intensive field studies.

Mr. Lodge, one of the Great Lakes region’s most distinguished scientists for years, is dead set on the accuracy of eDNA.

He has a hunch there are far more pieces of genetic material they’re missing than ones they’re getting wrong. The future, he said, is less about the need for better accuracy and more about improving the sensitivity of equipment and getting devices developed that are portable enough to take into the field for research that can be done closer to real time.

Addressing the threat

Meanwhile, congressmen and other public officials — including governors and state attorneys general — continue to slug it out over the politics and costs of addressing the Asian carp threat.

A report issued a year ago by the Army Corps of Engineers outlines several potential options, the most expensive being the $18 billion one to separate the Lake Michigan and Mississippi River watersheds. Though it is designed to help reduce flooding in Chicago, it hasn’t been widely supported by Illinois officials.

But there are other potential pathways for Asian carp, including the Eagle Marsh area of Fort Wayne, Ind., where the Wabash River — which is already filled with silver Asian carp, the species that leaps out of the water when startled by boat motors — can connect to the Maumee River when the water’s high. A tall fence has been erected as a barrier.

Several area congressmen, including Rep. Marcy Kaptur (D., Toledo), have gotten behind legislation introduced Feb. 26 by Rep. Candice Miller (R., Mich.) and Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D., Mich.) that calls for short-term measures and consideration of long-term solutions to the issue without impairing shipping.

Joel Brammeier, president and chief executive officer of the Chicago-based Alliance for the Great Lakes, said there is still “absolutely hope” of keeping Asian carp out of the Great Lakes, although he found it “deeply disappointing” the Corps of Engineers did not provide more direction in its 2014 report and that an advisory committee had to be formed to provide leadership.

“I do get concerned we’ve bided our time long enough,” Mr. Brammeier said.

Miss Kaptur said the corps “has dragged its feet for too long on this issue and now needs to step up.”

“Hydrologic separation is the only permanent solution to stop Asian carp from entering the Great Lakes through Chicago,” Miss Kaptur said.