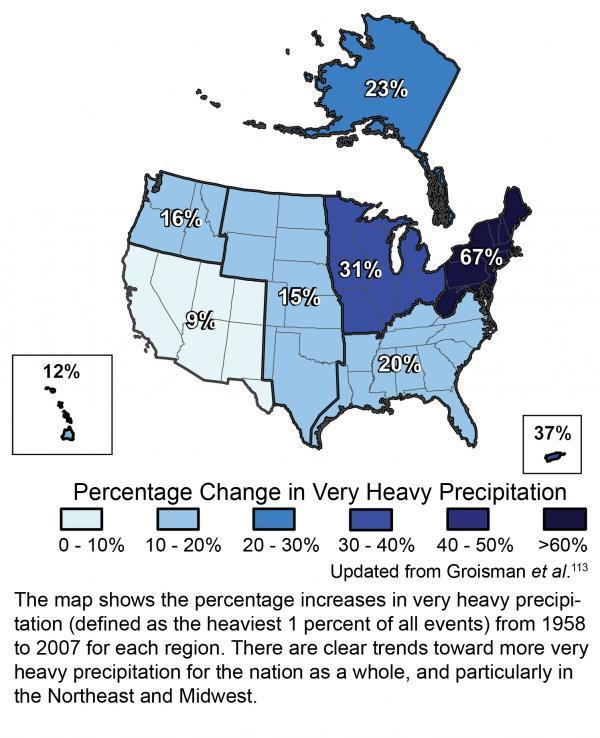

Connecticut and the Northeast region have gotten a lot more rain over the years. A report from the National Atmospheric and Oceanic Administration found a 67 percent increase since 1958, more than any other part of the country.

Now researchers at Yale University want to find out what happens to the chemical composition and water quality of the Connecticut River watershed and the Long Island Sound with more heavy rain.

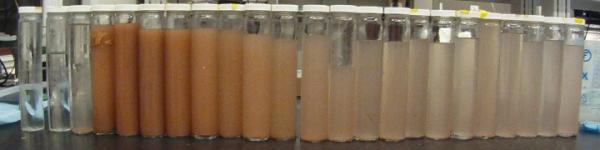

The five-year study focuses on something called dissolved organic matter, explained Peter Raymond, a professor of ecosystem ecology at Yale and lead investigator of the study. He said it's a lot like tea.

"Just like when you take tea leaves and dip it in water," Raymond said, "the water picks up a lot of dissolved organic matter, and turns your teacup water brown. As rain falls over a watershed and interacts with the soil, it picks up a lot of dissolved organic matter. When you go out and you see some water bodies that look like a cup of tea, that's dissolved organic matter coming off of the landscape into the water."

That includes the chemicals that bacteria, plants, and algae release to the soil. We don't know exactly what's in it, and how much more we can expect when it rains a lot more. That could change a lot of things, including water quality, how much light reaches the water and the amount of heavy metals.

To take one example from 2011, in just a few days, Hurricane Irene flushed out more than 40 percent of the dissolved organic matter that should have been flushed out in the whole year.

By studying the Connecticut River in detail, researchers hope to come up with better models of how this works. That means the northeast region will be better prepared for the effects of more intense storms because of climate change, according to Henry Gholz, a program director at the National Science Foundation, which is funding the study with a grant of around $3 million.

"Think of how we all -- whether it's individuals, or municipalities, or mayors of towns along rivers -- how we're continuously surprised at things that happen," Gholz said. "Floods...droughts; fish disappear; other fish that we don't want maybe invade; rivers turn colors; all these kinds of things happen, and we're surprised by them."

He said with better models, we can better predict "how things might or will change given changes in climate or changes in land use and other things that we do in watersheds, and we all live in watersheds."

And it's not just in Connecticut; New York City is also trying to figure out how a changing climate will affect what's in the water that eventually ends up in reservoirs, according to Peter Raymond of Yale.

As well as studying the effects of climate change, this investigation could also change the way we think about rivers, said Jennifer Tank, professor of biological sciences at the University of Notre Dame.

An aerial image shows the amount of sediment washed into Long Island Sound after Hurricane Irene.

"Right now," Tank said, "our approach has been to consider the headwaters [knee-deep] of river networks as being the kidneys. They filter carbon and nutrients before they move into river systems. Then we sort of treat river systems as if they are pipes, and they just transport things down. They're not doing work."

Tank said this study -- with hydrologists, biologists, and hydrogeochemists all working together -- should lead us to think about the whole river system.

Gholz of the NSF agreed. He said studies like this aren't common, and that the results will most likely be useful to other places too, not just the Connecticut River. He said, "It's the kind of study that will likely end up in textbooks about streams and rivers."